Baboons in captivity in Ancient Egypt: insights from a collection of mummies

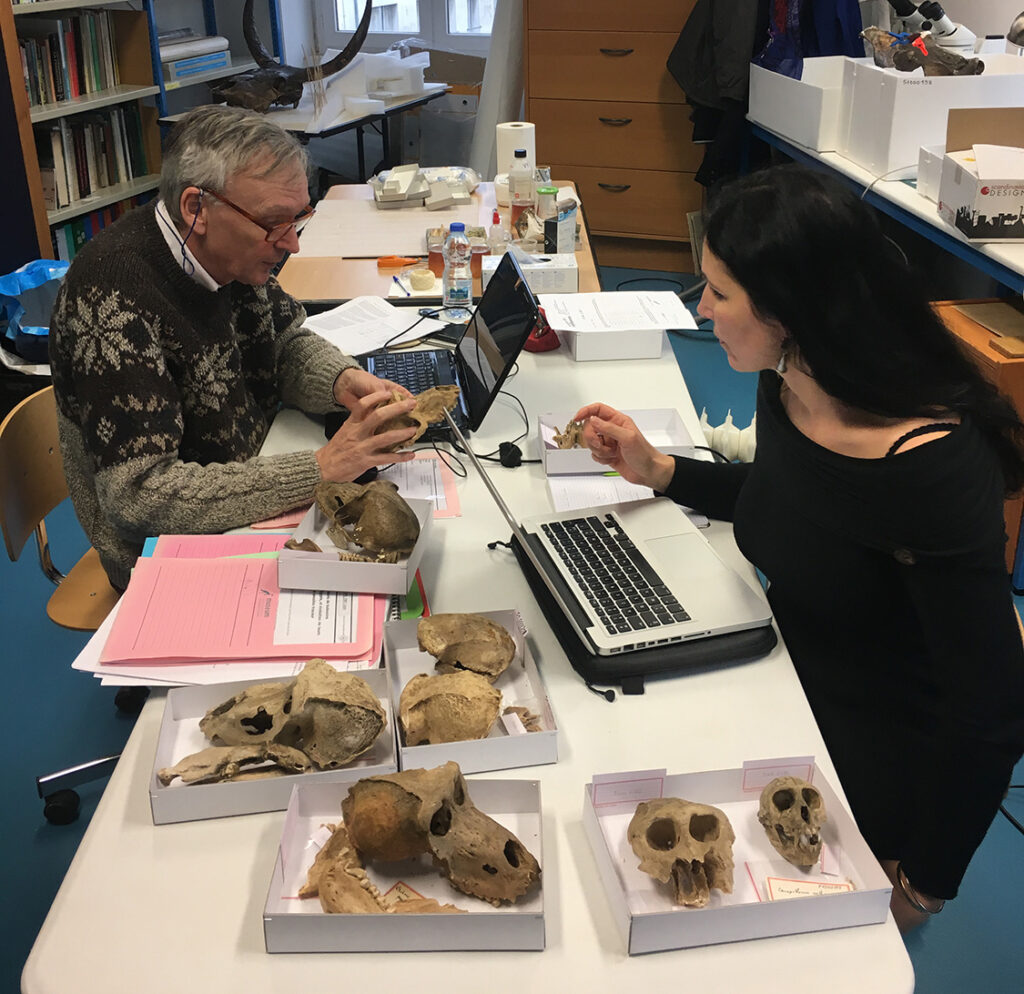

Skeletal pathologies in ancient Egyptian baboon mummies suggest health problems due to inadequate nutrition and chronic lack of sunlight. An international team led by the Belgian archaeozoologist Prof. Wim van Neer from the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences examined baboon mummies from Ancient Egypt, around 3,000 years old. Apparently, the animals suffered from various metabolic diseases caused by poor husbandry conditions. SNSB and LMU paleoanatomist Prof. Joris Peters, Director of the Bavarian Collection for Paleoanatomy in Munich, was also involved in the study. Prof. Peters is specialist of skeletal diseases in animals and helped to assess the various paleopathologies in these captive primates. The study was published today in PLoS ONE.

For over a millennium, from the 9th century BC to the 4th century AD, the ancient Egyptians venerated and mummified various animal species for religious and ritual purposes. Tens of millions of animal mummies were buried in Egypt’s underground necropolises. In many places, dogs, cats, sacred ibises and birds of prey were worshipped, but there were also burial sites for cattle, crocodiles and fish. Some of them even contain exotic animals such as baboons, Barbary apes and vervet monkeys, which were not native to Egypt. Not much is known about how these animals were acquired and kept.

The researchers led by Wim van Neer examined the skeletal remains representing at least 36 individual baboon from the ancient Egyptian site Gabbanat el-Qurud, the so-called Valley of the Monkeys on the west bank of Luxor. Radiocarbon dating revealed that the animals lived around 3,000 years ago. The mummy collection is kept in the Musée des Confluences, formerly Musée d’Histoire naturelle de Lyon.

Poor husbandry conditions

Most of the baboons examined were in a very poor state of health during lifetime. The animals’ bones showed lesions, deformations and other anomalies.

“We attribute these skeletal changes to the poor conditions in which the baboons were kept in captivity. Chronic lack of sunlight and poor nutrition apparently did not provide the animals with sufficient calcium and vitamin D and caused severe metabolic disorders that significantly impaired their skeletal development. Presumably the animals were kept in high walled, roofed enclosures without direct access to sunlight,” Prof. Joris Peters says.

“Almost all the animals in the baboon population from Gabbanat el-Qurud suffered from these metabolic disorders. We assume that these animals were born and raised in captivity. They were probably bred locally to meet the demand for animals for processional, oracular and other cult purposes,” Peters continues.

Skeletal deformities and pathologies in primates are also known from other animal cemeteries, such as the more or less contemporary Middle Egyptian animal necropolises of Tuna el-Gebel and Saqqara, and the much older Upper Egyptian site of Hierakonpolis (4,000-2,500 BC). The authors note that similar pathologies, age and sex distribution are seen in baboon remains from Saqqara and Tuna el-Gebel, suggesting a fairly consistent mode of captive keeping.

Further research

Additional analyses are essential to find out more details about the husbandry and origin of the ancient Egyptian baboons. The authors suggest, for example, further examinations of the microbiomes in the dental calculus to gain insights into the animals’ diet and the presence of microorganisms in the oral cavity. Genetic data from ancient DNA might reveal information on where the animals were caught in the wild and what breeding practices their keepers were employing.

Publication

Van Neer W, Udrescu M, Peters J, De Cupere B, Pasquali S, Porcier S (2023) Palaeopathological and demographic data reveal conditions of keeping of the ancient baboons at Gabbanat el-Qurud (Thebes, Egypt). PLoS ONE 18(12): e0294934. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0294934

Contact

Prof. Dr. Joris Peters

Lehrstuhl für Paläoanatomie, Domestikationsforschung und Geschichte der Tiermedizin der LMU München und

Staatssammlung für Paläoanatomie (SNSB-SPM)

Tel: +49 (0)89 / 2180 – 5711

E-Mail: peters@snsb.de

(Photo: J. Peters, SNSB)